She records the prevalence of syphilis in the yurts, she bites her fleas in half, and she is too busy keeping warm, getting food and sleep, to worry about having mystical revelations in the desert. She confesses to being tormented by the need to prove herself, and in a tight spot admits to trembling with fear like the rest of us. “With all the weight of the heavens over my sleeping body I shall learn what a roof is,” she writes. Maillart says that life is made real by simplifying it, in the company of simple peoples. (As for mountaineering, it is obviously a form of madness.) What is this escapism about? Is it a need to prove, or to “find”, oneself? To impress others? Is it hatred of the modern world? Or is it a romantic fantasy about other people’s lives? Hardships are routinely exaggerated and travel writers have become the heroes of their own stories.Īs one who endures heat, cold and hunger only when absolutely unavoidable, I find the persistent fascination with primitive living hard to explain. As Dervla Murphy (herself a doughty soloist) says in her introduction to Maillart’s book, adventure has become just another commodity. Expeditions are little more than organised Land Cruiser tours. The nomad yurts in which Maillart slept are now the tourist B-and-Bs of Central Asia. True nomadism is extinct and the wilderness has largely been tamed.

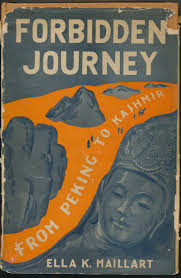

But in the age of cheap air fares, of the backpacking droves and the upmarket package tour, that nostalgia is not easily requited. Western nostalgia for the primitive life, reverence for the “noble savage”, is hardly new. Her book, written in the early 1930s and now re-issued, reminds us just how much the world has changed. In fact, Maillart had the company of four Muscovite friends for the first part of that trip.

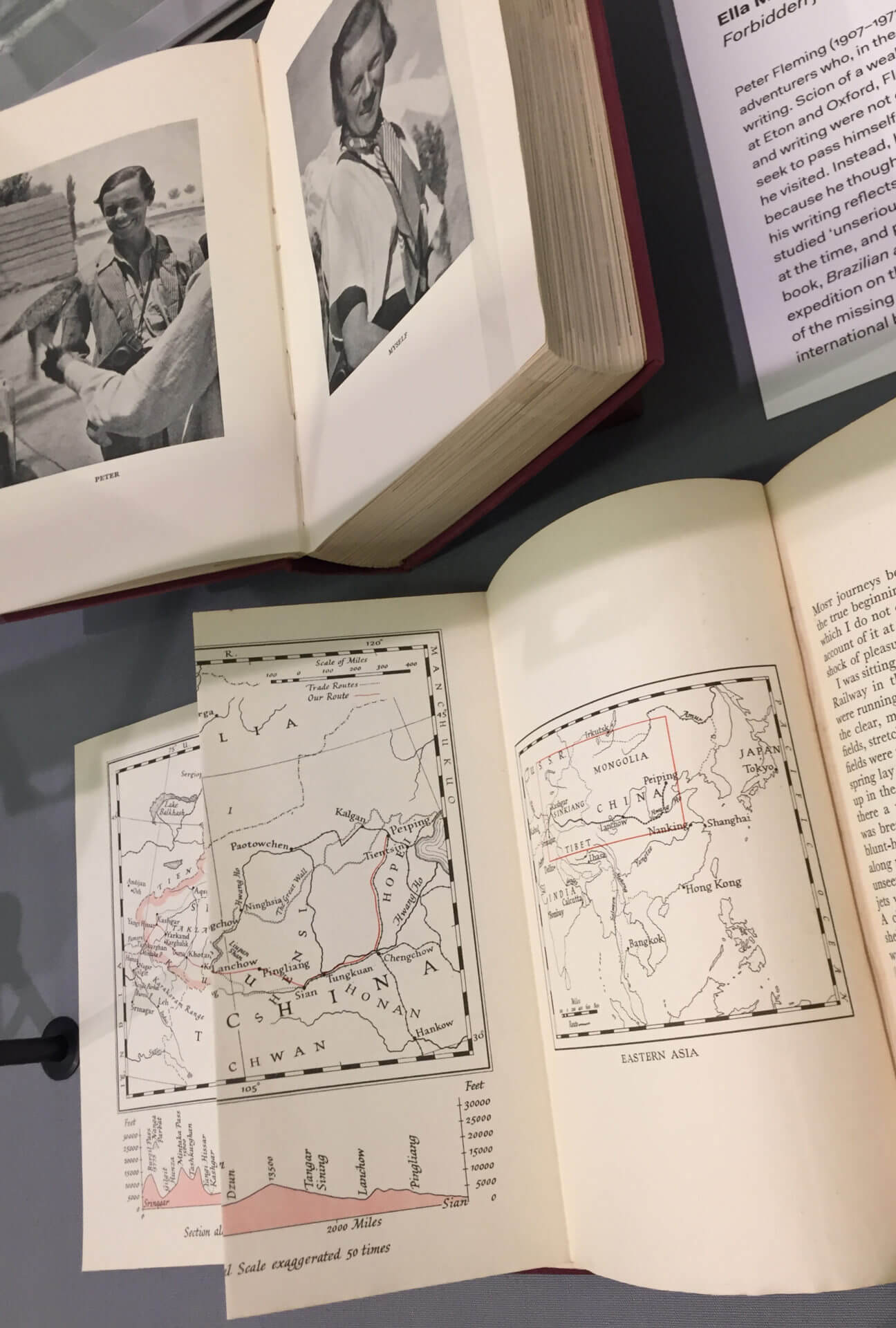

Fleming’s previous book had been called One’s Company Maillart’s had been Turkestan Solo, the story of her travels through Russian Turkestan. It had been with reluctance that they teamed up for this adventure, which produced a book apiece, since both made a fetish out of travelling alone (native guides did not count).

364 Language: English.Ella (“Kini”) Maillart is best known to English readers as the woman who accompanied Peter Fleming overland from Beijing to India via Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan in the 1930s.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)